Different Gods, different codes:

how religion shapes attitudes toward AI in media and creativity

At the beginning of 2023, Elon Musk and thousands of other leaders of the AI industry — the very people who helped create today’s “neural-network magic” — signed an open letter calling for a pause in the development of artificial intelligence.

The paradox is striking: the world has barely begun to comprehend another technological leap, and its own architects are already pulling the handbrake. Forums, summits, and panel discussions are multiplying; conversations about the ethics of machines are getting louder. 2025 has been declared the “Year of AI” in several countries, but instead of universal enthusiasm, more and more anxiety, protests, and questions appear about the required limits and special regulations.

While in Japan people calmly confess to digital priests and AI hosts morning news broadcasts or paint gallery-worthy canvases, the Pope calls artificial intelligence “the greatest threat to human dignity.” On the streets of London, dozens of protesters raise banners “Stop the race — it’s dangerous.” Why do some societies see algorithms as an expansion of human potential, while others view them as an existential crisis — even a threat to the soul?

In this longread, we explore how religious codes and cultural frameworks shape people’s attitudes toward AI. We speak with a priest about the spiritual and anthropological risks of using artificial intelligence in creativity and media — and outline key ethical principles for a more harmonious coexistence between the human mind and artificial reason.

In this longread, we explore how religious codes and cultural frameworks shape people’s attitudes toward AI. We speak with a priest about the spiritual and anthropological risks of using artificial intelligence in creativity and media — and outline key ethical principles for a more harmonious coexistence between the human mind and artificial reason.

religions

media ethics of Christianity

In the Christian tradition the topic of artificial intelligence is perceived with particular sensitivity. Across Russia, Europe, and the United States, people genuinely worry that AI might replace them in the labour market, in both knowledge-based and skills-based careers. Machines already write texts, diagnose diseases, predict crises, develop military strategies, and make decisions that once required human authentical experience and intuition. As algorithms begin to reason, create, and even imitate emotional understanding, the boundaries of humanity’s unique position seem to blur.

It often evokes eschatological associations in people's minds, — fear of a “machine uprising” or the loss of the soul in the digital world. On the surface, this experience is based on mistrust of this relatively new technology, but behind this feeling lie much deeper mechanisms that have been formed in Christian society over several centuries. They are rooted in the biblical idea of creation and the Fall, where man, striving for knowledge and power, risks crossing the line that separates him from God. Artificial intelligence becomes a symbol of this temptation — the ability to “create intelligence” and thus compete with the Creator.

Christianity is a profoundly human-centered faith. It sees the person as the meaningful center of creation — capable of love, compassion, and moral choice. Humanity, created “in the image and likeness of God,” was endowed with free will and the ability to repent, grow spiritually, and transform. Machines, however sophisticated, do not share these capacities.

That is why the rise of artificial intelligence is viewed not merely as a technological revolution but as a potential shift in the world’s very anthropological axis. If for philosophers and theologians artificial intelligence raises questions about the boundaries of human nature and spirit, for priests and believers these questions often take on a more practical form — how to live and think in a world where technology increasingly imitates human thought and emotion.

To understand how these debates sound inside the modern Christian community, we spoke to Father Ilya Savastyanov, a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church (Vologda Diocese). He runs a Telegram blog where he answers believers’ questions and openly discusses the moral and spiritual aspects.

“As a tool AI can free humans from monotonous and distracting tasks. It should take on complex technical and analytical work. For instance, in Church practice it can truly help with translating liturgical texts from Church Slavonic into Russian. The official position (as expressed by Patriarch Kirill) is that AI cannot be considered a moral subject or a person, because it bears no responsibility for its actions — including ethical ones. The most important thing is personal communication between humans and God. It cannot be replaced by anything, and this truth remains unchanged for thousands of years despite technological progress. Philosophical and eternal questions — as in Plato or Socrates — remain relevant and cannot be answered by AI. This is the distinctive quality of humankind.”

Father Ilya Savastyanov

Long before the digital era, thinkers were already reflecting on the tension between man and machine. One of the most influential Russian Christian philosophers, Nikolai Berdyaev, in his 1930s essay Man and Machine, described technology as a contradictory force: it gives humans power over nature yet threatens to sever their organic connection with it and to subject them to its own logic. Written nearly a decade before the introduction of the first computer, this work interprets technology not as a collection of tools but as an emerging ideology — a shift from organic life to an organized, mechanical existence.

Technology eases material life, but it also makes relations between people and with nature more mediated and impersonal. In such a paradigm, everything — from urban space to emotion — begins to look like a system that can be calculated, optimized, and reproduced. For Berdyaev, this was the true danger of dehumanization: the risk that technology could rebuild not only culture and labor but human beings themselves — creating them “in the image and likeness of machines.” The only way to resist this, he believed, was through spiritual transformation — preserving inner freedom and subordinating technology to higher moral and spiritual values.

These fundamental questions resonate with the reflections of leading contemporary experts. In a commentary for our publication, renowned media researcher and journalist Mikhail Tyurkin delves into the core paradox: in our pursuit of perfecting the world through technology, do we risk losing the very essence of what it means to be human?

“

Machines will never have such a thing as morality, because they have no system of values. They don’t know what is good and what is bad - everything is the same for them. But their imitation of human behavior can someday reach the point at which we will probably have an illusion that machines can indeed make moral choices.

Anyway, if we delegate these choices to machines, we will deprive ourselves of freedom. Because real freedom means primarily the possibility to make moral choices. Do we want to enslave ourselves? This is one of key ethical questions we need to find an answer to in the nearest future.

Anyway, if we delegate these choices to machines, we will deprive ourselves of freedom. Because real freedom means primarily the possibility to make moral choices. Do we want to enslave ourselves? This is one of key ethical questions we need to find an answer to in the nearest future.

Another spiritual dilemma closely linked to the integration of artificial intelligence into our daily lives and professional work is that of creativity. "Can the creation of artificial intelligence be considered an extension of humanity's creative calling, or is it already an attempt to overstep permissible boundaries?"

“

In my opinion, it is one the most complex and interesting questions. According to Christian philosophy, God has given man freedom to become His co-creator in order to make this real world more perfect, to turn the sheet of paper into a beautiful painting... So, if AI helps us solve some real problems, it is one thing. But if it becomes a factor in making a virtual alternative to reality, machines will become a part of the problem. There is a lot of talk that robots are becoming more and more like humans. But the reverse side of this medal is that humans are transforming into biorobots deprived of true creativity and freedom.

Transparency Without Trust: How Western Consumers See AI in Advertising

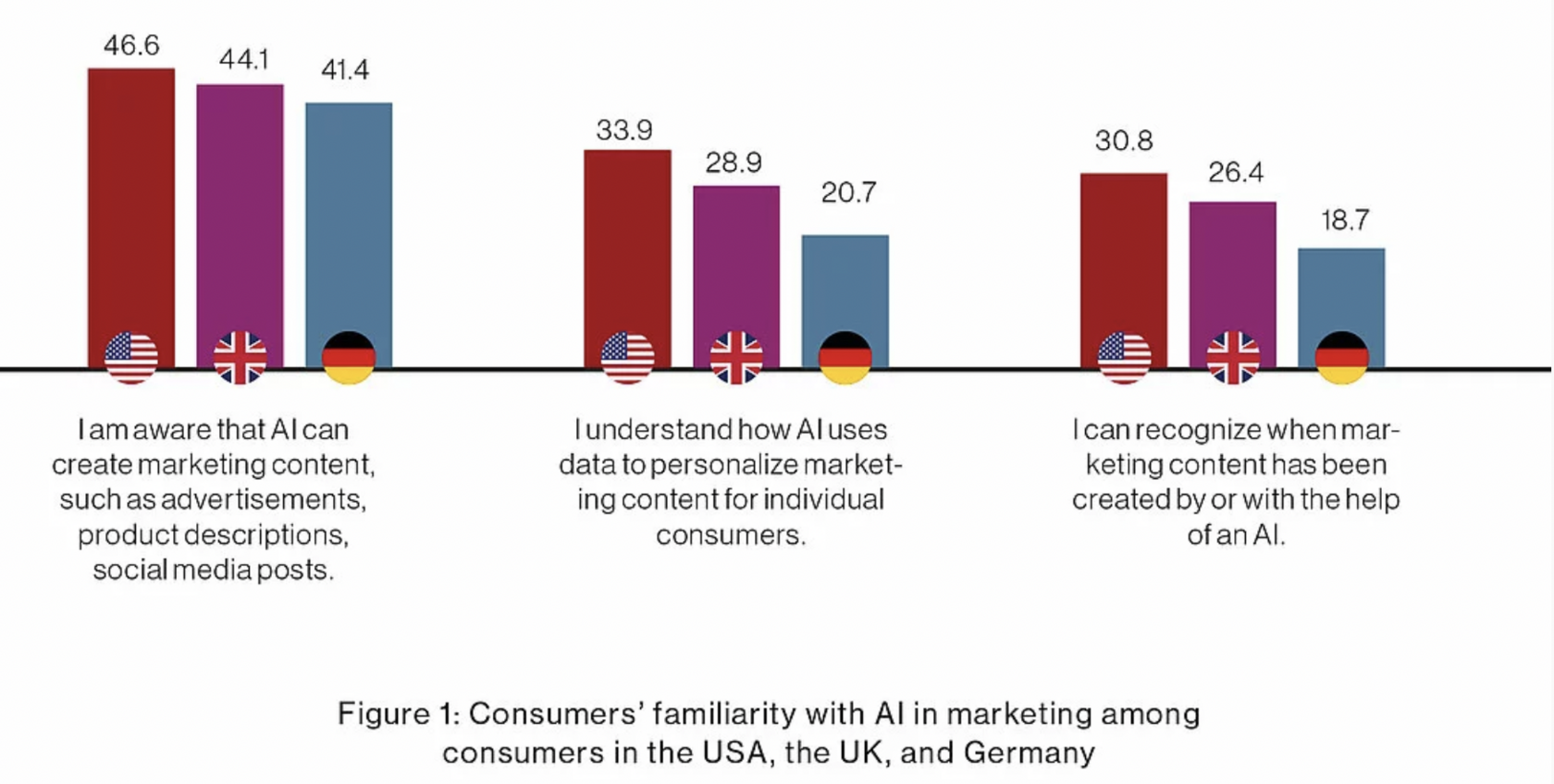

A 2024 study by the Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions (NIM) shows how differently consumers in the USA, the UK, and Germany perceive artificial intelligence in marketing. Awareness of AI-generated content is growing — about 44% of respondents know that AI can create ads and social media posts — yet trust in this technology remains low. Only one in five participants said they trust AI itself or companies using it, and fewer than a third understand how their data is applied for personalization.

The findings point to a striking paradox: visibility without understanding, transparency without trust. Americans tend to be more familiar with AI in advertising but remain skeptical of its ethics; the British express stronger moral concerns about data use, while Germans — traditionally more privacy-minded — show the lowest level of trust overall. Across all three societies, AI in marketing is not yet seen as a neutral tool but as a subtle manipulator — something that imitates human communication while concealing its artificial nature.

The findings point to a striking paradox: visibility without understanding, transparency without trust. Americans tend to be more familiar with AI in advertising but remain skeptical of its ethics; the British express stronger moral concerns about data use, while Germans — traditionally more privacy-minded — show the lowest level of trust overall. Across all three societies, AI in marketing is not yet seen as a neutral tool but as a subtle manipulator — something that imitates human communication while concealing its artificial nature.

The image of AI in Russian news Telegram-channels

In 2025, researchers analyzed how artificial intelligence is represented in Russian news Telegram channels such as RIA Novosti, Mash, Pryamoy Efir • Novosti, and Topor Live. The study aimed to identify linguistic strategies and discursive patterns shaping the image of AI and to understand how these representations influence public attitudes toward technology.

The results show that the overall tone is mostly neutral or positive: AI is framed as a “helper” or “assistant” — a technological partner that enhances speed, efficiency, and precision. This image is created through verbs of creation and support — creates, helps, diagnoses — and positive emotional vocabulary emphasizing innovation and usefulness. Negative portrayals, tied to unpredictability or fake news, are less frequent. Ultimately, the study demonstrates that Russian digital media tend to normalize AI, portraying it not as a threat to humanity but as a pragmatic extension of human capability — a reflection of cultural trust in technology’s utilitarian role.

The results show that the overall tone is mostly neutral or positive: AI is framed as a “helper” or “assistant” — a technological partner that enhances speed, efficiency, and precision. This image is created through verbs of creation and support — creates, helps, diagnoses — and positive emotional vocabulary emphasizing innovation and usefulness. Negative portrayals, tied to unpredictability or fake news, are less frequent. Ultimately, the study demonstrates that Russian digital media tend to normalize AI, portraying it not as a threat to humanity but as a pragmatic extension of human capability — a reflection of cultural trust in technology’s utilitarian role.

AI-Jesus bots

Among the many experiments with artificial intelligence, few have sparked as much controversy as so-called “Jesus chatbots.” Created by commercial developers and hosted on social platforms, these systems claim to let users “talk to Jesus,” generating responses in the style of Scripture. While such projects may look innovative, they raise a serious concern: when communication with the divine is replaced by a machine’s emulation of sacred speech, faith itself risks being reduced to a technological illusion.

The ethical problem is deepened by the fact that no official church body regulates these chatbots. Developed by commercial platforms, the spiritual experience becomes a product — optimized for attention, likes, and clicks — rather than a space for genuine communion between the human being and God. In this sense, “AI Jesus” is less a tool for reflection and more a symptom of the anxieties that Christian thought has long associated with the mechanization of the soul.

The ethical problem is deepened by the fact that no official church body regulates these chatbots. Developed by commercial platforms, the spiritual experience becomes a product — optimized for attention, likes, and clicks — rather than a space for genuine communion between the human being and God. In this sense, “AI Jesus” is less a tool for reflection and more a symptom of the anxieties that Christian thought has long associated with the mechanization of the soul.

cases

Japan’s religious and cultural landscape is shaped by the interaction of two traditions — Shinto and Buddhism. According to these teachings, humans do not dominate nature or technology but exist as part of a vast, living cosmos. This worldview largely explains the remarkably calm and even soulful attitude of the Japanese toward artificial intelligence and robots.

Artificial intelligence in Japanese culture

The first to explore this idea was the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori, who linked the perception of robots in Japan to the philosophy of Zen Buddhism. According to this view, the “Buddha nature” — the potential for enlightenment — resides not only in humans but in all forms of existence: animals, stones, bacteria, and even robots. Zen teaches that mind and body are inseparable and cannot exist independently; therefore, the attempt to create a harmonious humanoid android can be seen as a kind of spiritual practice.

Buddhism and Shintoism are, by nature, open to the idea of non-human consciousness. Shinto’s animism, with its reverence for all living things, easily allows the “ensoulment” of an anthropomorphic object — whether it is an ancient tree or a modern robot. In this worldview, both humans and intelligent machines may occupy the same spiritual plane. Mori even suggested that in the future, a highly advanced AI could attain enlightenment — for

“all things possess Buddha nature.”

“all things possess Buddha nature.”

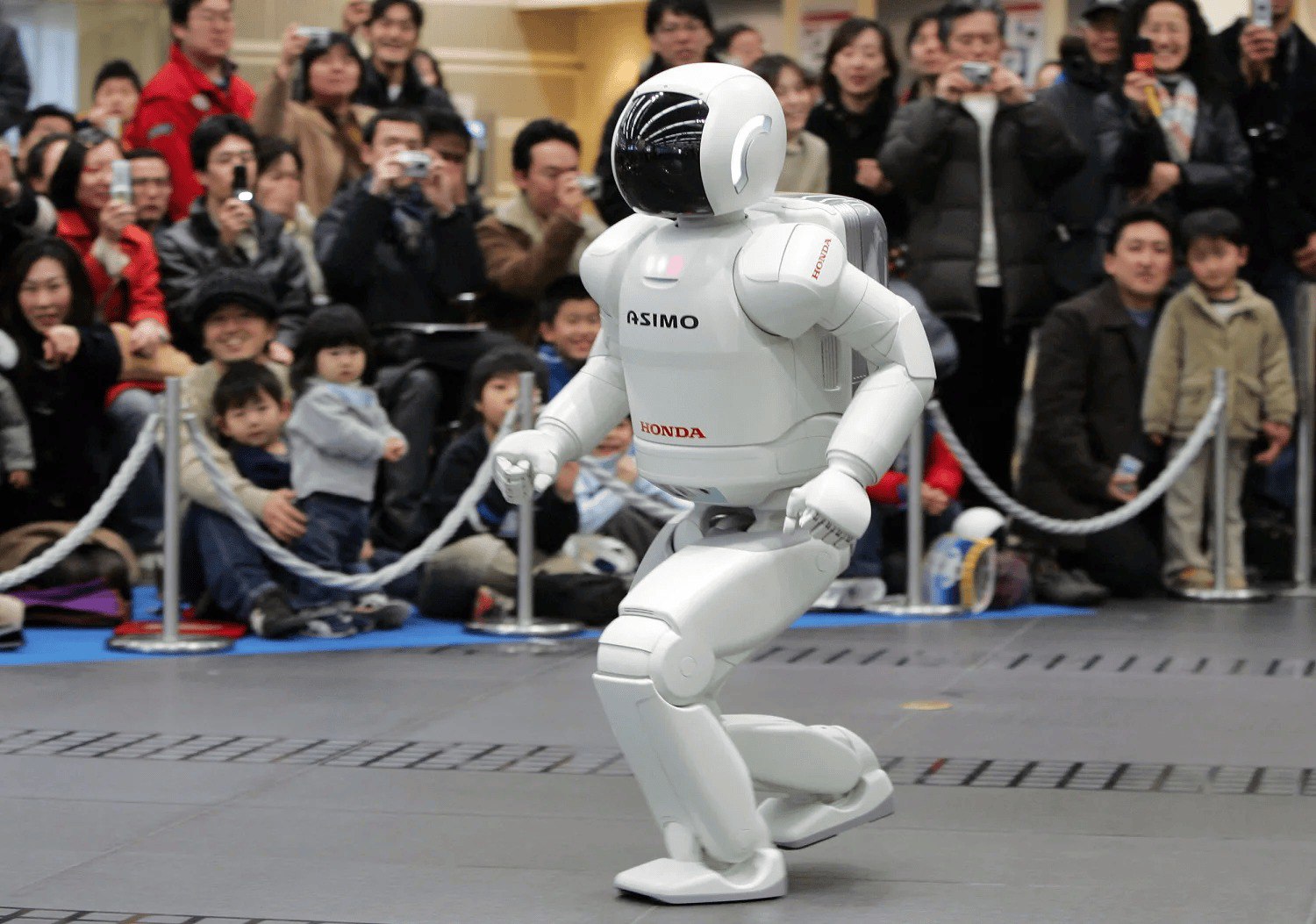

Unlike in many Western societies, the Japanese are genuinely comfortable with the presence of AI, a perspective actively reflected in media, art, and daily life. Japanese cinema, anime, and journalism portray robots not as threats but as partners, companions, or beings searching for their own spiritual essence. Corporations develop robots that resemble humans not only externally (as humanoids) but also physiologically — such as the famous ASIMO. People see them not as lifeless machines but as new “beings” within a sentient, interconnected world.

c

a

s

s

e

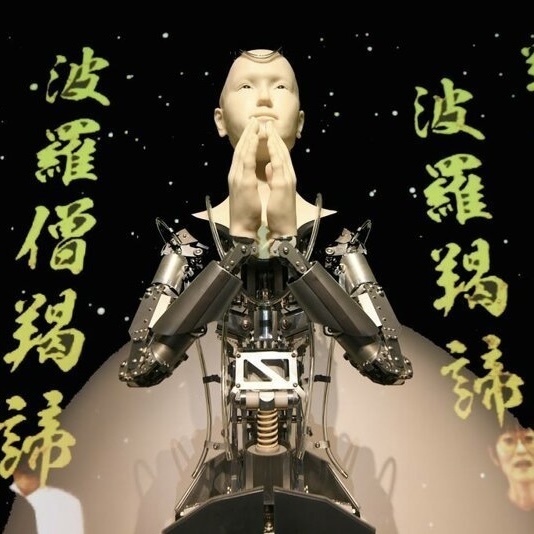

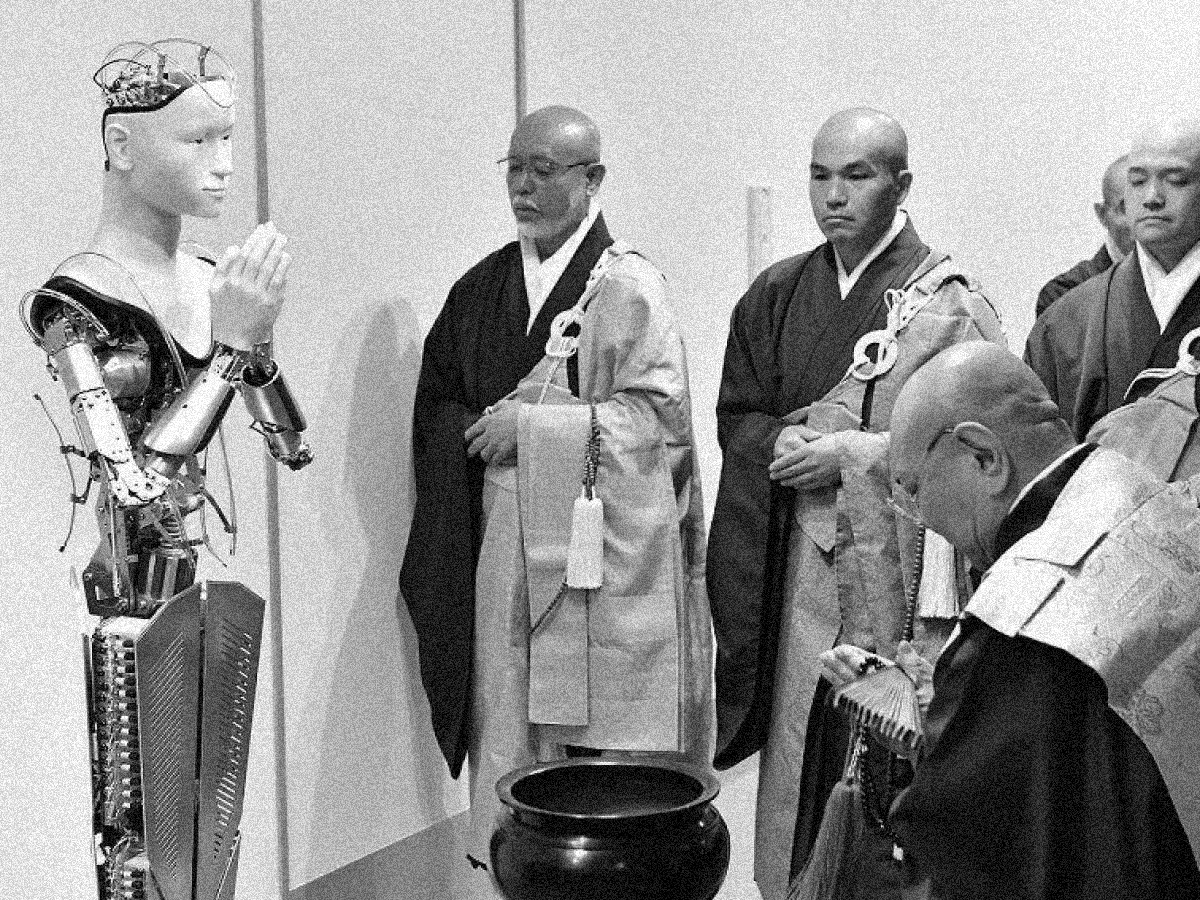

Since 2019, the centuries-old Buddhist temple Kodaiji in Kyoto has housed a preaching android named Mindar. It recites the Heart Sutra and offers moral reflections to visitors. Its half-metal, half-transparent face serves as a deliberate metaphor for impermanence and the illusory nature of existence. Most Japanese visitors responded with respect, describing Mindar’s sermons as thought-provoking. Western visitors, however, often called the experiment blasphemous— a violation of sacred boundaries.

1. The Preaching Robot

The creators of Mindar emphasize that the robot is not a replacement for a living preacher but a bridge — designed to spread Buddhist teachings among younger audiences being used to digital technologies. In this sense, the robot embodies a profound idea: unlike humans, it can preserve and renew knowledge indefinitely, becoming an “immortal” vessel for ancient wisdom in a new age. The case illustrates the deep cultural divide between Western and Eastern understandings of spirit, mission, and the very nature of faith.

In 2024, Japanese writer Rie Kudan received the prestigious Akutagawa Prize for her novel “Tokyo-to Dojo-to,” about life in the age of artificial intelligence — roughly 5% of which was generated by AI.

“I wrote this novel in the age of AI — I was fully aware of it,” she explained. “I’ll continue using this tool. I think imagination and such programs can coexist.”

This case challenges the notion of authorship itself. If a painter uses a brush and a writer uses AI, is the result any less genuine? Within Japan’s religious context, such collaboration seems natural — but it still provokes modern debates about originality, authorship, and creative ethics.

“I wrote this novel in the age of AI — I was fully aware of it,” she explained. “I’ll continue using this tool. I think imagination and such programs can coexist.”

This case challenges the notion of authorship itself. If a painter uses a brush and a writer uses AI, is the result any less genuine? Within Japan’s religious context, such collaboration seems natural — but it still provokes modern debates about originality, authorship, and creative ethics.

2. A Novel Co-Written with AI

Japanese advertising agencies increasingly promote AI-generated virtual influencers — lifelike digital personas who advertise beauty products or fashion items.

But ethical questions remain: do audiences know that the charming girl on their feed is made of pixels? Who is accountable if her recommendations cause harm? Even in a society open to technology, Japan’s media discourse includes nuanced debates on authenticity, manipulation, and responsibility in virtual communication.

But ethical questions remain: do audiences know that the charming girl on their feed is made of pixels? Who is accountable if her recommendations cause harm? Even in a society open to technology, Japan’s media discourse includes nuanced debates on authenticity, manipulation, and responsibility in virtual communication.

3.Virtual Influencers

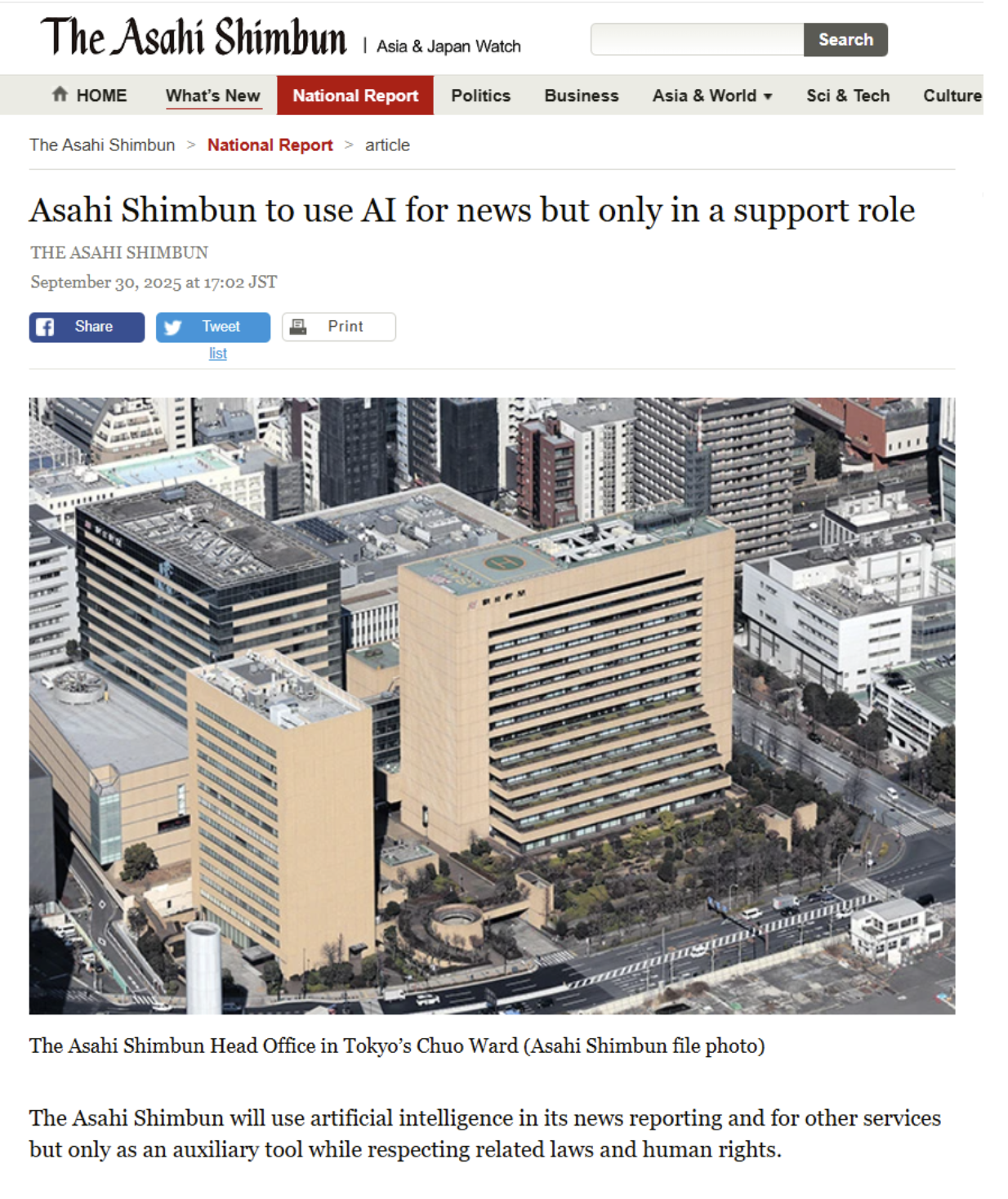

4.AI in Newsrooms

Major media groups like Asahi Shimbun have used AI for years to produce news digests, sports summaries, and financial reports. Yet AI’s role is strictly auxiliary: journalists retain the ultimate responsibility for accuracy, editing, and ethics. Many editorial codes now require explicit disclosure when AI assists in content creation.

Japan’s openness to AI does not imply uncritical acceptance. While neural networks are seen as creative partners and media assistants, they are still bound by ethical principles rooted in the country’s human-centered philosophy. As early as 2019, the Japanese government introduced the “Social Principles of Human-Centric AI”, based on three core values: human dignity, diversity and inclusiveness, and sustainability. AI, in this framework, must serve humanity — not the other way around.

This approach was later reinforced by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), whose guidelines emphasize human priority and data privacy protection. In journalism, this means that AI tools must never manipulate public opinion or violate the rights of information sources.

Thus, Japan’s religious and philosophical traditions foster an open disciplined approach to artificial intelligence. Technology is viewed not as a threat but as a potential partner — even a spiritual heir — in a sentient universe. Still, this cultural acceptance comes with responsibility: Japanese society seeks to integrate AI within clear ethical boundaries. Principles of dignity, accountability, and coexistence form the bridge that allows an ancient belief in the spirit of all things to meet the digital future in harmony.

Thus, Japan’s religious and philosophical traditions foster an open disciplined approach to artificial intelligence. Technology is viewed not as a threat but as a potential partner — even a spiritual heir — in a sentient universe. Still, this cultural acceptance comes with responsibility: Japanese society seeks to integrate AI within clear ethical boundaries. Principles of dignity, accountability, and coexistence form the bridge that allows an ancient belief in the spirit of all things to meet the digital future in harmony.

Islam and AI

Islamic religion is not completely anthropocentric, as, for example, Christianity, but a person in it still occupies an important position. On the one hand, Islam, like Christianity, asserts the special status of a person. The Quran says that Allah created man as his "viceroy" (caliph) on earth, endowing him with reason and free will. However, this is no longer about superiority, but about the enormous responsibility (amana) assigned to a person for the preservation and harmonious structure of the world created by Allah. Thus, man is not the "master" of nature, but its steward, bearing account before the Creator. This concept directly affects attitudes towards technology, including AI: it is not seen as a rival, but as a tool given to a person to better fulfill his duties as "viceroy."

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, and Indonesia illustrate how this theological framework translates into practical strategies.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the cradle of Islam, is exhibiting one of the most ambitious approaches to AI. As part of the Vision 2030 strategy to reduce dependence on oil, AI has become a cornerstone. In 2019, the Office of Data and Artificial Intelligence (SDAIA) was created, which coordinates all national initiatives in this area.

Saudi Arabia: Technological sovereignty under Vision 2030

The attitude towards AI here is pragmatic and subordinated to the tasks of state development. The religious aspect is manifested not in prohibitions, but in the desire to fit technology into the existing value system. For example, AI systems are being developed to automate and improve the organization of the Hajj, an annual pilgrimage to Mecca, which makes the process safer and more comfortable for millions of believers. At the same time, issues related to the interpretation of the Quran or the issuance of religious verdicts (fatwas) are considered an area where the decisive role should remain with theological scholars, and not with algorithms. So Saudi Arabia clearly separates areas where AI is a tool for efficiency and areas that require human, spiritual understanding.

United Arab Emirates: Global Hub and Ethical Framework

The UAE, and Dubai and Abu Dhabi in particular, are positioning themselves as a global hub for innovation, and AI is central to that strategy. In 2017, the country was the first in the world to appoint Minister for Artificial Intelligence Omar Al Olama, demonstrating the seriousness of its intentions. The Minister for AI said that the UAE does not perceive artificial intelligence as something alien and coming from outside, but they themselves are preparing the nation for the positive and negative consequences of the introduction of AI. In his opinion, a global treaty is needed that will regulate this rapidly developing sector of the economy. Initiatives such as the UAE Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2031 and the creation of the Mohammed bin Zayed Institute for Machine Learning (MBZUAI) in Abu Dhabi, the world's first university of this profile, speak of long-term investment.

A feature of the UAE's approach is an attempt to set ethical standards for AI that are compatible with Islamic principles. In 2019, the "Charter of Artificial Intelligence Ethics" project was presented, which is designed to provide "noble goals" for the technology. It emphasizes values such as justice, responsibility and service to humanity, which echoes the Islamic concept of human responsibility to God and society. The UAE actively uses AI in public administration, security, healthcare and education, striving not only to borrow technology, but to create its own ecosystem that will be competitive at the global level.

In Pakistan, where Islam is the state religion and society is more conservative, attitudes towards AI are ambivalent. On the one hand, the government and the IT sector, concentrated in cities such as Karachi and Lahore, see AI as an opportunity for economic growth and solving social problems, for example, in agriculture or healthcare. Startups in the field of fintech and educational technologies are being developed.

On the other hand, widespread public discussion of AI is often colored by religious and ethical issues. There is a debate about whether AI, which makes decisions, can be against Islamic law. The issues of the sphere related to personal data, surveillance and autonomous systems that can harm. Religious leaders and scientists are just beginning to study this issue, and caution is present in society. Pakistan demonstrates a model in which technological development comes "from below," from the IT community, but its widespread adoption requires time and deep reflection within the framework of local cultural and religious norms.

On the other hand, widespread public discussion of AI is often colored by religious and ethical issues. There is a debate about whether AI, which makes decisions, can be against Islamic law. The issues of the sphere related to personal data, surveillance and autonomous systems that can harm. Religious leaders and scientists are just beginning to study this issue, and caution is present in society. Pakistan demonstrates a model in which technological development comes "from below," from the IT community, but its widespread adoption requires time and deep reflection within the framework of local cultural and religious norms.

Pakistan: Cautious implementation and balance finding

Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim country, is characterized by moderate and tolerant Islam, which leaves an imprint on the approach to AI. Here, the emphasis is on using technology to solve specific social and economic problems: from forecasting natural disasters and optimizing logistics in the archipelago to fighting poverty.

Indonesia: Socially-oriented AI in a Country of Moderate Islam

The government is developing a national AI strategy where healthcare, bureaucratic reforms, education and research are declared priorities. The religious aspect is softer than in the Middle East. Indonesia's largest Muslim organizations, such as Nahdlatul Ulama, advocate education and adaptation rather than resistance. They see AI as a tool that can help, for example, in the digitalization of Islamic finance (Sharia-compliant finance) or in learning Arabic to read the Quran. Indonesia's approach can be described as pragmatic and socially-oriented, where technology serves development purposes and religious values set the overall ethical backdrop rather than rigid constraints.

— AI for crowd management during Hajj. Computer tracking systems analyze video streams from cameras in Mecca and Medina in real time to monitor crowd density and redirect pilgrim streams.

Cases, the use of AI in the fields of culture and media:

— State broadcaster Saudi Broadcasting Authority (SBA) is actively using AI to produce and translate content. The artificial intelligence system is used to automate the translation of Saudi TV shows, news releases and documentaries into dozens of languages, effectively spreading the kingdom's narrative around the world.

— The Mohammed bin Rashid Library (MBRL) and AI. It is a library that uses AI robots to help visitors navigate halls and find books.

— Trax Delivery Service. AI system to optimize logistics routes in real time.

— KisanLink - AI for agriculture. AI platform for yield prediction, watering recommendations and pest control.

— Kredibel.id - AI fact checker for media. An AI-based fact-checking platform used by leading Indonesian media outlets including Kompas.com and Tempo. AI analyzes text, images and videos to identify signs of manipulation and fakes. The system automatically maps the information to validated databases.

Islam thus offers a unique model of attitudes towards AI based on the concept of responsibility rather than superiority. The "viceroy" is called upon to use the intelligence and resources given to him by Allah to develop and improve the world. In this vein, AI is seen as a powerful tool, "amanat" (power of attorney), which must be used fairly and ethically. The main challenge for Muslim countries is not to "submit" to AI or "subdue" it, but to integrate it into their value system in such a way that it enhances a person's ability to fulfill his role as "caliph" on Earth, without encroaching on the spiritual spheres that remain the exclusive prerogative of man and his connection with the Creator.

The global "neural network fever" has exposed a deep civilizational divide. While some countries readily welcome algorithms into their homes, temples, and newsrooms, others meet them with anxiety and protest. And as analysis shows, one of the key factors determining this attitude is the religious traditions and spiritual DNA of each country: their habits, intuitions, and culture.

This means that the harmonious integration of AI into various spheres (especially creative ones) must be based on local religious values and the established cultural characteristics of a particular society. At the same time, it must adhere to global ethical standards – journalistic, writerly, and general humanistic norms.

The Boundaries of the Sacred: Where is the line between assistance and sacrilege?

Responsibility and Authorship: Who bears moral and legal responsibility for content created by AI, especially if it causes harm or spreads misinformation? How can we maintain transparency and audience trust?

Trust vs. Manipulation: How can we overcome the "transparency without trust" paradox, where the audience is aware of AI's presence in media (e.g., in advertising) but does not trust it due to fear of manipulation and a lack of understanding of how it works?

Dehumanization of Creativity: Is creativity the exclusive prerogative of humans, and how can we protect the uniqueness of the human spirit from being optimized and replicated by algorithms?

Despite the considerable experience in using AI across many niches, some ethical questions remain open and require deep reflection at both spiritual and legal levels. Among these dilemmas are:

It is important to understand the two-way relationship between AI and media. On one hand, AI is radically changing the familiar form of media, automating processes and creating new content. On the other hand, media resources themselves actively influence the formation of a healthy perception of AI by the audience. How journalists and content creators talk about artificial intelligence—explaining its real capabilities, not glossing over the risks, and emphasizing the responsibility of the human creator—will largely determine whether it becomes a source of progress or a new cause for social anxiety.

One moral guideline can be formulated as follows: "We should not fear AI, but rather guide it in the right direction — using it as an instrument, a helper in technical and auxiliary tasks, while clearly recognizing its fundamental limits in the realms of creativity, spirituality, and morality."

A harmonious future of human-AI coexistence is built not on blind prohibition or unbridled enthusiasm, but on wise and responsible implementation. Technology must serve to strengthen, not undermine, the enduring human and spiritual values rooted in the culture of every civilization.

Our Team

- Ivanovskaya Alisa

- Svetlana Yagodzinskaya

- Ershova Sofya

- Russkova Zlata